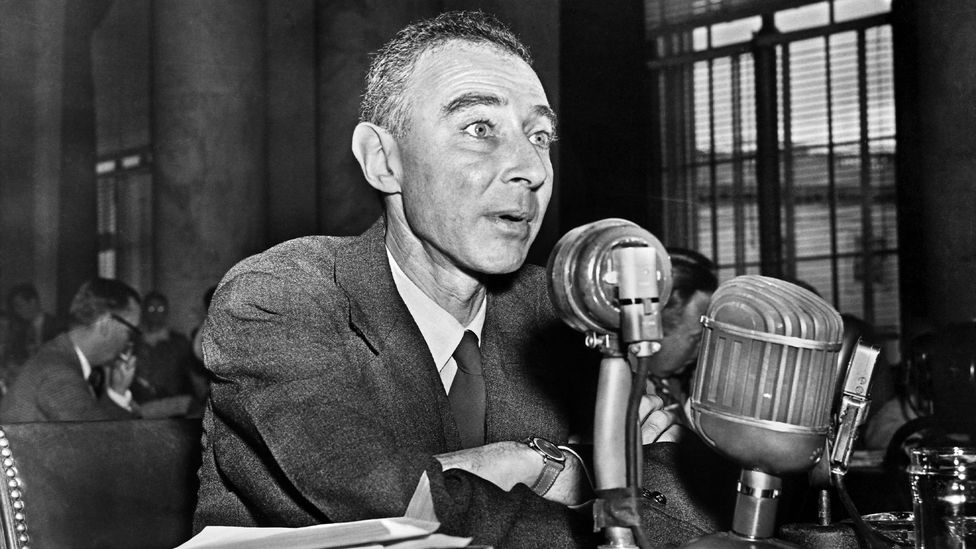

When the Soviets exploded their first atomic bomb in 1949, US President Harry Truman ordered American scientists to embark on a new programme to build a hydrogen bomb, whose nuclear explosion could be 1,000 times more powerful than an atomic bomb. Oppenheimer, the government's chief scientific advisor on nuclear policy and defence, objected on moral and practical grounds, reportedly telling Truman, "I feel I have blood on my hands." Oppenheimer's defiance ultimately made him a chief target of the US' anti-communist hysteria during the Cold War. In the spring of 1954, he endured an exhaustive four-week interrogation that questioned his US loyalty and ultimately stripped him of his security clearance. (The US government would ultimately clear his name 68 years later.)

According to Bird, a now-fully-white-haired Oppenheimer was left "humiliated, terribly wounded and physically and psychologically exhausted". So, that summer, the disgraced physicist left his Princeton, New Jersey, home, boarded a 72ft ketch with his wife and two children and set sail for St John.

"He was escaping – escaping the notoriety of being the father of the atomic bomb, but also the notoriety that plagued him after the '54 trial, the suspicions of disloyalty, of being a Communist or perhaps a spy," Bird said. "When they saw the island for the first time, [Oppenheimer] fell in love with St John … so, he went back the following year and eventually found some property on the beach and built a very simple, spartan cabin, and it's where he spent the rest of his life – you know, many months of the year, both in the winter, but sometimes in the spring and summers … it wasn't about penance; it was about getting back to the physicality of the natural world."

Oppenheimer's St John

St John couldn't be further from the life Oppenheimer left – and that was the point. Oppenheimer grew up in a posh home in Manhattan's Upper West side with three maids, a chauffeur and Van Gogh paintings hanging on the walls. When the family landed on the Manhattan-sized island in July 1954, Bird and Sherwin write that there were virtually no phones or electricity, and peacocks and donkeys roamed the dirt streets. St John had only been a US territory for 37 years and 90% of its 800 residents were the descendants of formerly enslaved people the island's previous Danish landlords had kidnapped from Africa to work on their sugar and cotton plantations. The island's first bar wouldn't be built for two more years, and its largest building was a one-storey West Indian gingerbread-style cottage.